If you want to know government’s priorities, don’t be swayed by eloquent speeches from politicians, take a close look at the budget. Plans on how government intends to generate, allocate and spend public revenue in a manner that can hurt or protect the poor are revealed publicly. As Zimbabwe is endowed with abundant mineral wealth, a depletable public asset, it is critical to scrutinise the budget to see how government is leveraging mineral assets to promote broad based socio-economic development. After all, the theme for the Annual Pre-Budget Seminar, 08-12 November 2017, held at Elephant Hills, Victoria Falls was “Consolidation of Economic Development and Transformation Through Domestic Resource Mobilisation and Utilisation.”

By Mukasiri Sibanda

As a member of the Tax Justice Network Africa, the Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association (ZELA), a lead organisation on mineral resource governance at national and regional level, has strong interest in the 2018 national budget statement, themed “Towards a New Economic Order.” A pregnant theme that induces excitement and apprehension at the same time. Change by nature can result in opportunities for progression or threats for regression. So, what can we learn about development opportunities or threats from the 2018 national budget statementthrough a mineral resource governance perspective?

Curbing corruption and rent seeking behaviour in the mining sector

The budget missed the opportunity to embrace mineral revenue transparency best practice like the Extractive Industry Transparency Industry (EITI) to fight corruption and rent seeking behaviour in the mining sector. Mining agreements should be made public, including payments made to various government institutions by mining companies and beneficial owners of mining activities. For a government that prides itself on having strong political will to fight corruption, it is regrettable that an opportunity was squandered to help exorcise the ghost of “missing $15 billion” Marange diamond revenue.

By making public mining agreements, citizens can pressure government and mining companies to sign good deals that avoid skewing mining benefits in favour of corrupt public officials and corporates. Disclosure of various payments made to government institutions gives citizens the power to follow the money to hold to account government institutions on service delivery. As an example, through Caledonia’s Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act (ESTMA) report, taxes paid to Gwanda Rural District Council (GRDC), Rural Electrification Agency, Ministry of Mines and ZIMRA are publicly disclosed.

Platinum royalty rate reduced from 10% to 2.5%

The budget stated that Special Mining Lease Agreements (SMLAs) provide for a 2.5% royalty rate for some group of Platinum Group of Metals (PGMs) mining companies. Unfortunately, the budget masked the beneficiary mining companies of this fiscal arrangements which undermines the Public Financial Management Act (PFMA) prescribed PGMs royalty rates-platinum 10%, other precious metals 4%-palladium, rhodium, ruthenium, iridium, and osmium, and 2% for base metals like nickel.

To enhance fair competition amongst platinum miners, the budget slashed platinum royalty rate to 2.5% until August 2019. The budget failed to explain why August 2019. However, from Zimplats’ 2017 integrated report, we can learn that the company’s SMLA expires in August 2019. Thereafter, it can be renewed for two periods of 10 years each. The budget left the public in suspense on what will happen after August 2019. Is government going to continue with tax incentives for PGMs mining houses or not.

If not managed well, tax incentives can be harmful as noted by the blog- Disputes expose poor mining agreements. In 2015, Zimbabwe Revenue Authority (ZIMRA)’s annual revenue performance report revealed massive cost of the 2.5% royalty rate provided by SMLA to the public purse.

By making PGMs houses pay 2.5% royalty rates, it means that government has forgone mineral royalties from the exploitation of PGMs since there is a 2.5% export incentive scheme for mineral export earnings. Zimplats received a $14 million export incentive from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017 according to the company’s 2017 integrated report.

It is vital to note that the reduction of platinum royalty rate is the last point in the budget. This raises some eyebrows as to the involvement of the new Minister of Mines and Mining Development, Winston Chitando, formerly Mimosa platinum mine’ executive chairman. Mimosa mine is the only producing platinum mine which was not enjoying the preferential royalty rate since it is not a holder of a SMLA. Notably, it was unfair for Mimosa platinum mine to continue paying a 10% royalty rate whilst other platinum mines were enjoying a 2.5% preferential royalty rate. Government was supposed to renegotiate with PGMs houses with SMLA to comply with the 10% royalty rate prescribed by the PFMA instead of slashing the royalty rates to 2.5%.

Export tax to promote mineral value addition and beneficiation

To optimise benefits from mineral wealth extraction, value addition and beneficiation of mineral is critical. Interestingly the budget gave an example of lithium concentrate with a grading of 5 to 6% lithium oxide through off take agreements for US$600 per tonne. When beneficiated, resultant lithium carbonate is sold at prices ranging from US$15,000 to US$20,000 per tonne. From this example, by exporting raw minerals, the country is forgoing foreign currency earnings, tax revenue, domestic investment finance and jobs.

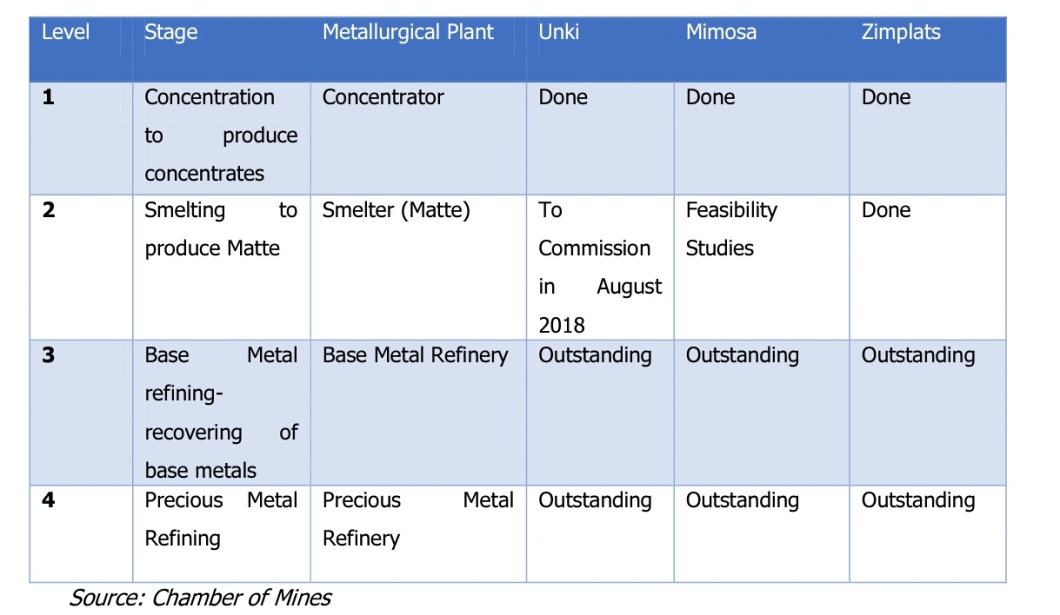

In 2015 government introduced 15% export on raw platinum export to encourage beneficiation and value addition. The export tax was suspended until December 2017 to allow PGMs players to implement agreed plans with government as detailed below.

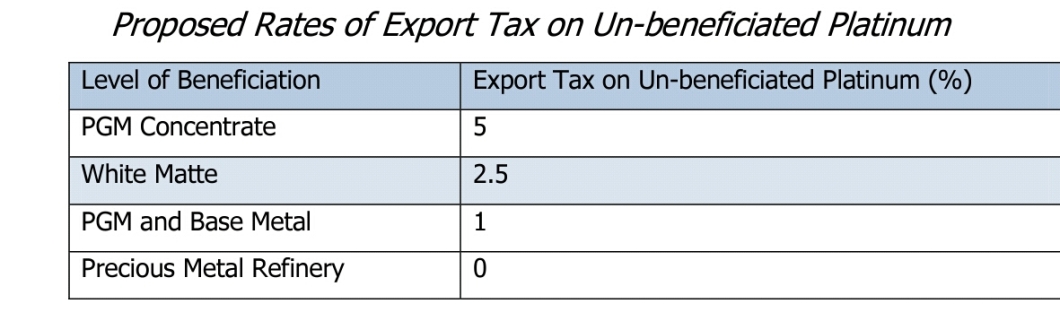

The 15% export incentive scheme failed to reward progressivity in beneficiation and value addition of PGMs. For example, Zimplats which exports platinum matte was treated the same as entities exporting platinum concentrates. By promoting a progressive export tax regime, the 2018 national budget statement made a commendable step. However, the sharp drop of export tax from 15% threshold to 5% may not be warranted.

Another commendable move is that export tax on raw mineral exports was extended to lithium and black granite with effect from 1 January 2019. The export tax on black granite is progressive as shown below.

| Dimensional Stone | Uncut | Cut only | Cut and polished |

| Export Tax (%) | 5 | 2.5 | 0 |

Export tax on gross value of exported lithium was pegged at 5%,

Review of mining fees and charges

Ground rental fee applicable to diamond concessions was reviewed from US$3,000 to $225 per hectare per annum. The review of mining fees and charges was only limited to the diamond sector. Artisanal and small-scale gold miners who demanded the review of fees for several permits required in the mining sector like prospecting license ($200), explosives purchase permit ($500), and explosives storage permit ($500) among others.

It is interesting to note that government has strong interest in vast Marange diamond fields through the Zimbabwe Consolidated Diamond Company (ZCDC). This brings to attention the issue of how government is handling conflicting objectives as a regulator and a player. The review of ground diamond ground rental fees could have been motivated by the desire to give ZCDC a life line.

Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Output Surpasses Output of Primary Gold Producers

17,163 kilograms of gold were delivered to Fidelity Printers and Refineries (FPR) between January and September 2017. Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining (ASGM) accounted for 51% share of the total gold deliveries in the same period. According the budget, ASGM production was boosted by government interventions like $40 million gold mobilisation fund and efforts to plug revenue leakages through joint compliance monitoring.

In light of the significant contribution of ASGM to the economy, it is unfortunate that the budget failed to respond to the key asks of many players in the ASGM sector as noted during the public pre-budget consultations held by PPCME in Bubi, Zvishavane and Mutoko districts. ASGM players want government to subsidise the costs of exploration by purchasing drilling rigs; to reduce the costs of multiple permits that criminalises a source of livelihood for 500,000 direct beneficiaries and 3 million indirect beneficiaries of ASGM; and to promote mechanisation of ASGM operations.

Indigenisation now restricted to platinum and diamond sector

The 51/49 indigenisation threshold in the extractive sector is now applicable only to the diamond and platinum sectors. Perhaps this came as an admission that the indigenisation scheme has failed to work seeing that only one company, Caledonia’ Blanket mine is fully compliant with the indigenisation model. To date, only 2 out of 61 community share ownership trust received share certificates.

The analysis of Zimplats’ 2017 integrated report: 11 things CSOs can learn makes an interesting observation concerning what to expect if the company is fully indigenised.

Thin capitalisation redefined

To promote investments considering the prevailing liquidity challenges, the budget redefined thin capitalisation to exclude locally contracted debt in the determination of debt equity ratio (3:1) prescribed by the Income Tax Act. The arm’s length principle applies. Meaning there are safeguards on paper to manage abuse through related party transaction. Interest accrued on debt element above the debt equity ratio is not an allowable deduction for the purposes of calculating taxable income.

When a company prefers to fund its activities through debt than owners’ equity, it leads to thin capitalisation. If not managed well, thin capitalisation erodes taxable income. Instead of investing owners’ equity to earn dividends, owners can make use related party transactions to fund their operations through debt to earn interest whether the company is profitable or not.

Expanding the scope of institutions to be audited by the Auditor General

The Auditor General’s 2016 report on state owned enterprise highlighted the challenges faced in terms of acquiring audited financial statement for Anjin to verify gross annual diamond sales used to compute depleting fees. By proposing expanding the scope of work of the Auditor General in the PFMA in line with Section 309 (2) (b) of the Constitution, to include government controlled entities like Anjin, there is scope for greater transparency and accountability in the management of mineral revenue. According to the 2012 annual report of the Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC), the corporation has 10% shareholding in Anjin, while Chinese firm Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Company owns 50% and the remainder is owned by the government. However, it is strongly suspected that Zimbabwe Defense Industries (ZDI) owns the mystery 40% shareholding in Anjin.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, during the pre-budget consultations, ZELA made its written submission to Parliament, particularly the Portfolio Committee on Mines and Mines and Energy titled 2018 National Budget Expectations: The Quest to Make Mineral Wealth Work for All: African Mining Vision (AMV). Main issues that ZELA raised include; adoption or adaption of the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI), resources for the mining computerised title, and support for Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining (ASGM) amongst others. ASGM players also made their contributions during the budget consultations mainly on exorbitant fees for multiple permits which are criminalising their livelihoods. It is sad that feedback from the budget on outcomes of the public consultations is lacking. Whilst input of large scale investors has a significant footprint in the budget like tax incentives, and the review of the indigenisation policy. FDI is needed to turnaround the economy particularly the capital-intensive mining sector. However, there is need for a policy mix that attracts FDI and mobilising much needed domestic finance for development.